I stuck to what was true, except that I didn’t include anything impossible. I wrote about what it was like on the playing field. How there were no teachers. How anything could happen. How anything had been happening for a long time now. I mentioned the lightning because there would be the patch of black glass on the ground ...

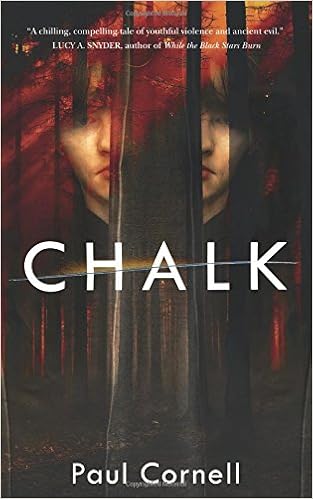

A horror novel about growing up in the 1980s: cod in butter sauce, Feast lollies, Bananarama, school discos. These things, in hindsight, are horrific in their own right, but Paul Cornell weaves a truly chilling story around the mundane details of Andrew Waggoner's school and home life, 1982-3.

The Amazon blurb describes this as 'a brutal exploration of bullying in Margaret Thatcher's England': well, yes, in the sense that the Bible is an exploration of God saying 'let there be light'. There is a lot more to the story than bullying, though that's where it starts: Andrew Waggoner is set upon by a group of bullies, after the Halloween disco, and maimed. He goes home -- can't tell his parents, because it would mean the end of their hopes for him, and also because he's embarrassed and simultaneously protective -- and washes the blood from his clothes, and stares out of his bedroom window into the night, out to the Downs with their earthlights and chalk figures.

And something sees him.

It's possible to read Andrew's new doppelganger, Waggoner, as a psychological rather than a magical manifestation. Waggoner occupies the same space as Andrew, and nobody but Andrew can see him. Waggoner behaves badly, and Andrew has to restrain him. Sometimes Andrew fails, and Waggoner enacts a series of bloody reprisals on Andrew's behalf.

As the year circles round to Halloween, there are indications that something bigger is happening around the edges of Andrew's story. The sense of creeping wrongness is subtly and effectively introduced. (I'd have liked just a little more about what was happening, what had happened long ago, on the downs: but the story doesn't need it.) Meanwhile, Andrew is trying to get through his mock exams, work out which music he's supposed to like, and befriend Angie, who is cool and interesting and who scries using the week's number one hit single. (Oh Lord, Rene and Renata.)

The finale felt slightly too rushed, though otherwise very satisfactory on both mundane and extraordinary levels. But what will stay with me about this book is the portrayal of what it was like to be an unpopular kid in the early 80s: Andrew's mingled embarrassment and protectiveness towards his parents, who only want the best for him; the fear of being seen by schoolmates outside school, where you can be judged; the sense that the adult world is an alien place from which no help should be sought, for it won't come; the way parents lie to their children, to be kind. Andrew doesn't know or care about politics, but he's acutely aware of class tensions. His mother, and especially his father, are at once central and peripheral to the story: like politics, they are incomprehensible and he doesn't pay a great deal of attention to them.

The bad thing that happens to Angie felt, on one level, like a false note: it's almost a cliche. But on the underlying mythic level, it makes a horrible kind of sense.

Highly recommended but not always nice.

No comments:

Post a Comment